All products featured are independently chosen by us. However, SoundGuys may receive a commission on orders placed through its retail links. See our ethics statement.

Is it illegal to drive with headphones on?

March 20, 2023

If you’re a frequent driver, you’ve probably seen someone at a red light or on the freeway with headphones on. The experience probably stuck out to you because that seems like a dangerous thing to do. It can’t possibly be legal, right?

Well, if you live in the US, chances are really good that even if it’s completely nonsensical, it isn’t explicitly forbidden in the state where you live—with a catch.

Heads up!

Times change and humans are fallible. The following was published on March 20, 2023 and every effort was made to link the statutes for each state directly (when and where they exist). However, this information may be out of date or less certain than it may appear here. Always check with you local Department of Motor Vehicles to verify information before treating what you read on the internet as infallible.

The law differs from state to state

Just like it is with pretty much any set of dangerous actions, where it’s illegal to drive with headphones on varies from state to state. If something is legal in Wyoming, that doesn’t mean it’s kosher in Colorado, for example.

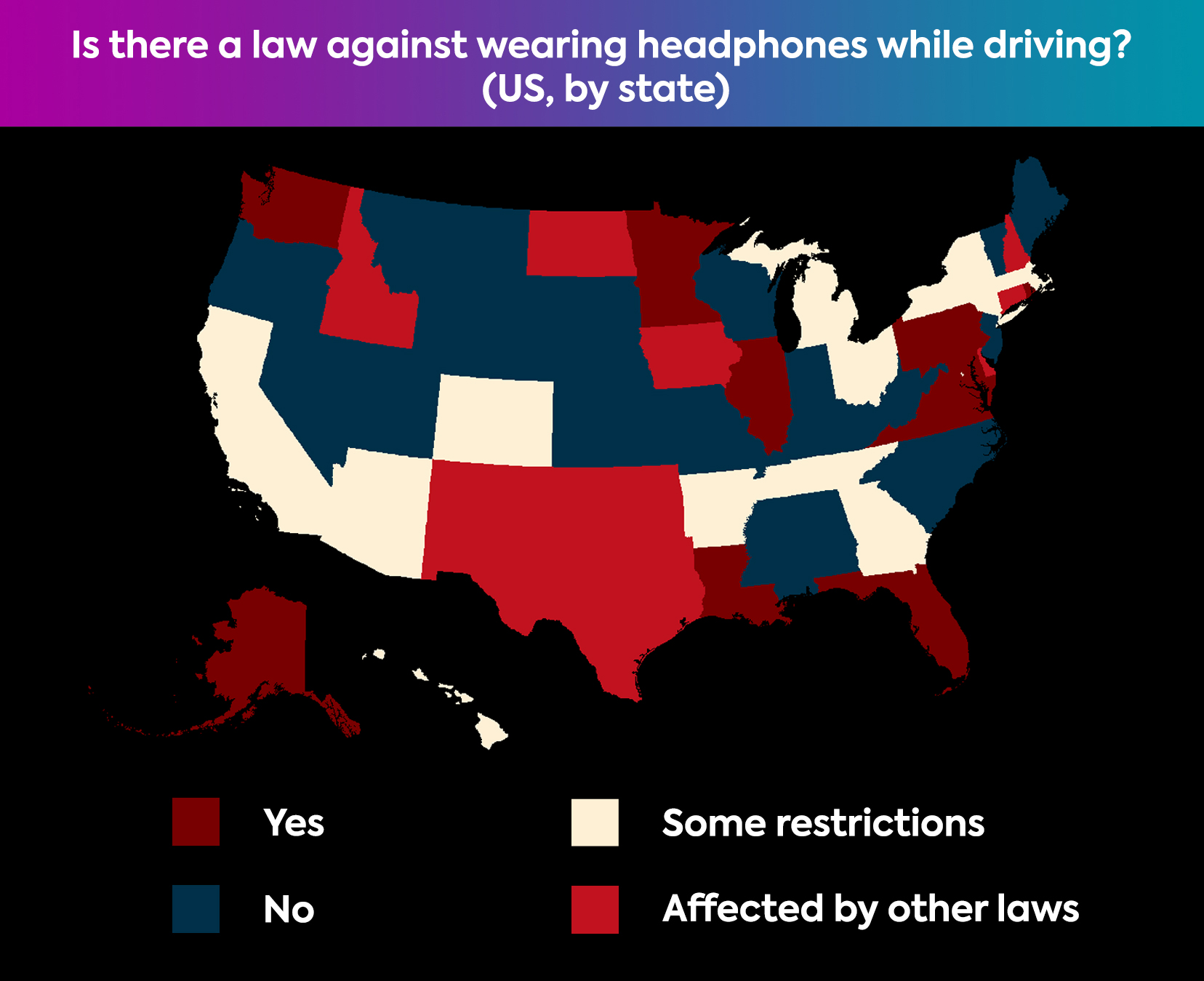

To save time, I’ve compiled a map of states and where it’s illegal to drive with headphones to get us started. Dark red shows states that have made explicit laws against all headphone use by drivers, bright red states have distracted or impaired driving laws that likely cover headphone use, white states are states with some restrictions on the activity, and blue states don’t currently have a restriction on headphone use while driving.

| State | Headphones explicitly banned while driving? |

|---|---|

Alabama | No |

Alaska | |

Arizona | No, with caveats |

Arkansas | No, with caveat that you don't communicate with them wirelessly. |

California | |

Colorado | |

Connecticut | |

Delaware | |

District of Columbia | |

Florida | |

Georgia | |

Hawaii | |

Idaho | |

Illinois | |

Indiana | No |

Iowa | No, but may run afoul of distracted driving laws. |

Kansas | No |

Kentucky | No |

Louisiana | |

Maine | No |

Maryland | |

Massachusetts | |

Michigan | No, but could be considered as careless driving at the discretion of the official. |

Minnesota | |

Mississippi | No |

Missouri | No |

Montana | No |

Nebraska | No |

Nevada | No |

New Hampshire | No, but may run afoul of negligence laws. |

New Jersey | No |

New Mexico | No, but may run afoul of distracted driving laws. |

New York | |

North Carolina | No |

North Dakota | |

Ohio | |

Oklahoma | No, but may run afoul of distracted driving laws. |

Oregon | No |

Pennsylvania | |

Rhode Island | |

South Carolina | No |

South Dakota | No |

Tennessee | No, with caveats |

Texas | No, but likely runs afoul of reckless driving laws. |

Utah | No |

Vermont | No |

Virginia | |

Washington | |

West Virginia | No |

Wisconsin | No |

Wyoming | No |

Some exceptions to the rules

Of course, there are exceptions to just about every rule. In states where there are only some restrictions on using headphones while driving, they’re pretty much all designed to allow single-ear Bluetooth headsets so you can still talk to someone on the phone. Additionally, states are very averse to banning hearing assistive devices like hearing aids or cochlear implants. Several more states also stipulate that you can’t listen to music through earpieces or headphones even if their use isn’t explicitly banned. Some states like Montana and New Mexico also have additional restrictions based on which town you’re in.

In the map above, almost all the states with “some restrictions” allow you to wear headphones or earphones if and only if you only occlude one ear, or use the product wired. It takes a while for laws to catch up to the realities of newer tech.

Listening to music on headphones while driving is a bad idea

It is always a bad idea to use entertainment products that affect how well you can pay attention to the road. It’s never a good idea to use headphones or earphones to listen to music while driving, because you can inadvertently distract yourself by doing so. At SoundGuys, we want you to get good headphones you’ll use and like, but we also don’t want you to be a danger to yourself and others while using them.

Even if what you’re doing isn’t explicitly prohibited, you may still be breaking the law

If you’re wondering about whether or not something is legal to do in a car, ask yourself if it distracts you from paying attention to the road, or makes it harder to pay full attention to your surroundings. If yes: it’s an activity that makes your driving less safe. Even if the exact thing you’re doing isn’t explicitly illegal, sometimes the natural consequences of that act are. States like New Hampshire and Texas, for example, have fairly broad ability to tack on stiffer penalties to behavior that would make a driver more dangerous to those around them in the event of a collision.

There are many professionals and regular folk with different needs that require the use of at least one earbud or other devices. With the line blurring on which products are okay to use on the road: it’s worth knowing what in particular makes something a hazard. How you use these products matters—but the law may not always agree.

A hearing impairment isn’t a driving impairment

Before we launch into the following sections it’s important to note that we’re not talking about hearing impaired drivers. We’re talking about distracted drivers.

Hearing impairments have been used in the past to deny the hard of hearing and deaf the right to drive, but there are a number of ways that these drivers can meet—or exceed—the ability of a hearing driver on the road. For example, having to adapt to life without hearing often correlates to much better peripheral vision and touch sensitivity—allowing hearing impaired folks greater ability to react to hazards that others may not notice, because they’re too used to hearing being their dominant cue for that hazard.

Additionally, there are other items to help perceive possible hazards like over-wide rear view mirrors or wide-angle mirrors to improve field of vision while on the road. Smartwatches like the Apple Watch also will often have maps integration that can tell you through haptic feedback whether to turn left or right instead of giving you the auditory cue. The only complication that merits mention here is that you may need a letter or icon on your driver’s license (like in the province of Quebec, for example) to indicate a hearing impairment, but that’s more to inform an officer at a traffic stop of the fact that they need to be aware of this when communicating with the driver than anything else. The law in your state (New York, for example) could also require certain equipment depending on an administered test. Often, they’ll just require you to use a full-view mirror—which isn’t exactly something I’d complain about on all cars.

It is not illegal (nor should it be) to drive with an absence of hearing. A distraction is another thing entirely because it impedes your attention—it’s not a problem caused by hearing difficulty.

Noise attenuation plus music equals increased perception distance

Because listening to music while also making the outside world around you comparatively much quieter makes it easier for you to take your attention away from the road, you are giving yourself what’s called a cognitive distraction. Examples of other cognitive distractions like texting might be more obvious because they require taking your eyes off the road, but for those for whom hearing is a primary source of experiential information, listening to music with headphones on is not much different.

Though your ears are only one way to perceive the outside world (and therefore not the only sense you should care about while driving), your brain can easily filter out unwanted information—like quiet noises when listening to music. To underscore this point, Ford recently led an experiment with University College in London with 2,000 participants to measure the perception plus reaction times of drivers. Participants using headphones to listen to music were 4.2 seconds slower to identify and respond to a hazard on the road than those who didn’t, on average.

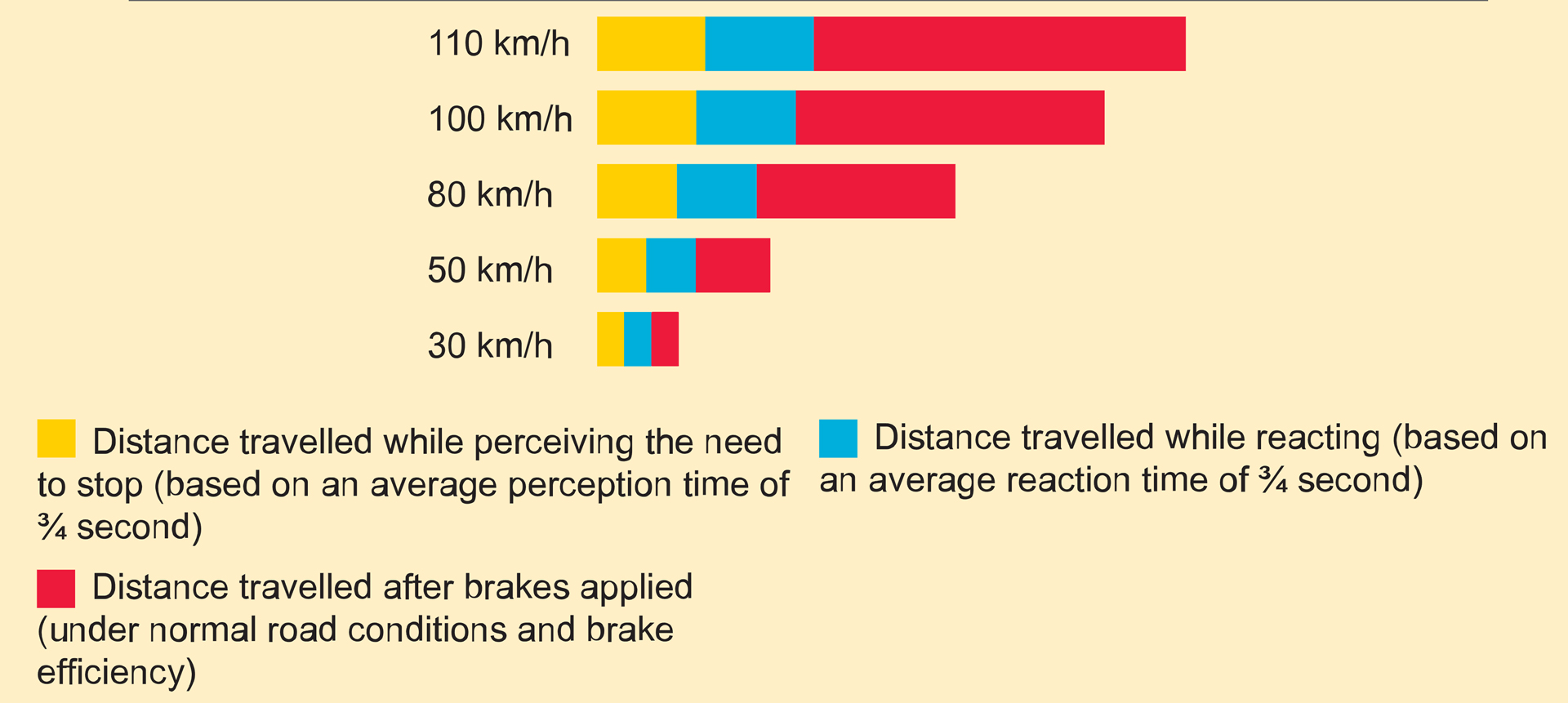

If you encounter a hazard on the road, the total distance it takes to bring your vehicle to a complete stop is called “stopping distance.” Your total stopping distance isn’t just how long it takes your car to stop moving once you slam on the brakes, though. It’s a sum of three three distances:

- How long you travel while noticing a hazard (perception distance).

- Plus how far you travel while it takes your brain to act on said hazard (reaction distance).

- Plus your your car’s stopping distance.

When you consider that the faster you’re traveling the longer it takes for your vehicle to come to a complete stop, it becomes clear how important keeping that perception distance to a minimum is. The sooner you can start braking, the better chance you have to avoid the hazard.

You can play around with this online calculator, but a general outline for ideal conditions can be interpreted like this:

| Stopping distance (ft.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Speed (mph) | Stopping distance (ft.) Normal driver (1.5sec) | Tired driver (2sec) | Driver with headphones playing music (5.7sec) |

10 | Stopping distance (ft.) 26.7 | 34.1 | 88.5 |

20 | Stopping distance (ft.) 63.15 | 77.83 | 186.5 |

30 | Stopping distance (ft.) 109 | 131.1 | 294 |

40 | Stopping distance (ft.) 164.5 | 193.9 | 411.1 |

50 | Stopping distance (ft.) 229.6 | 266.26 | 537.8 |

60 | Stopping distance (ft.) 304.2 | 348.2 | 674 |

70 | Stopping distance (ft.) 388.3 | 439.7 | 819.8 |

The 5.7 second figure is derived from the above listed study of the normal driver’s perception time (1.5 seconds) plus the delay in perception time of studied drivers listening to music with headphones (4.2 seconds on average). None of the perception or reaction time figures are absolute or representative of every person, but are based in sourced estimates from other sources.

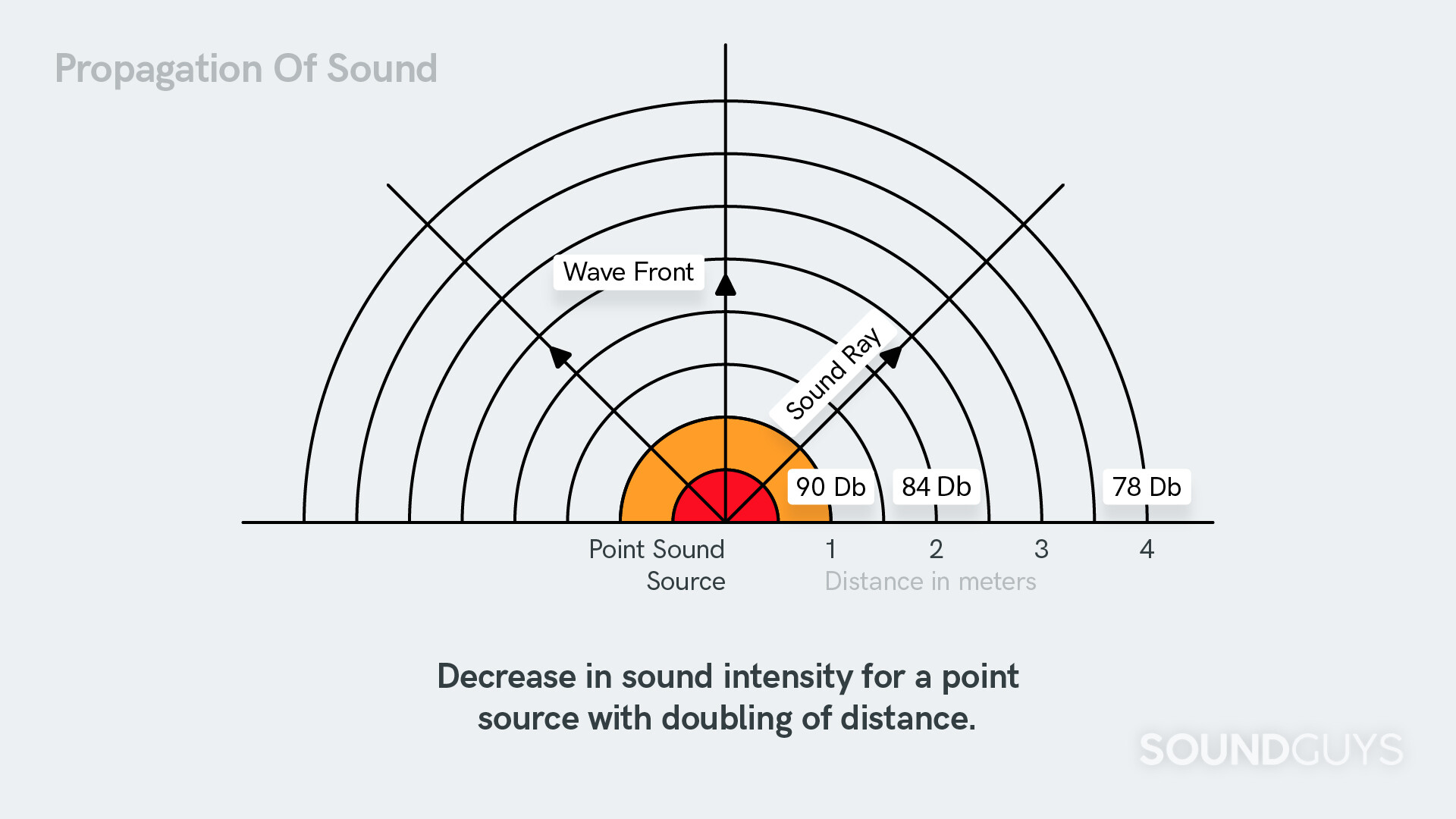

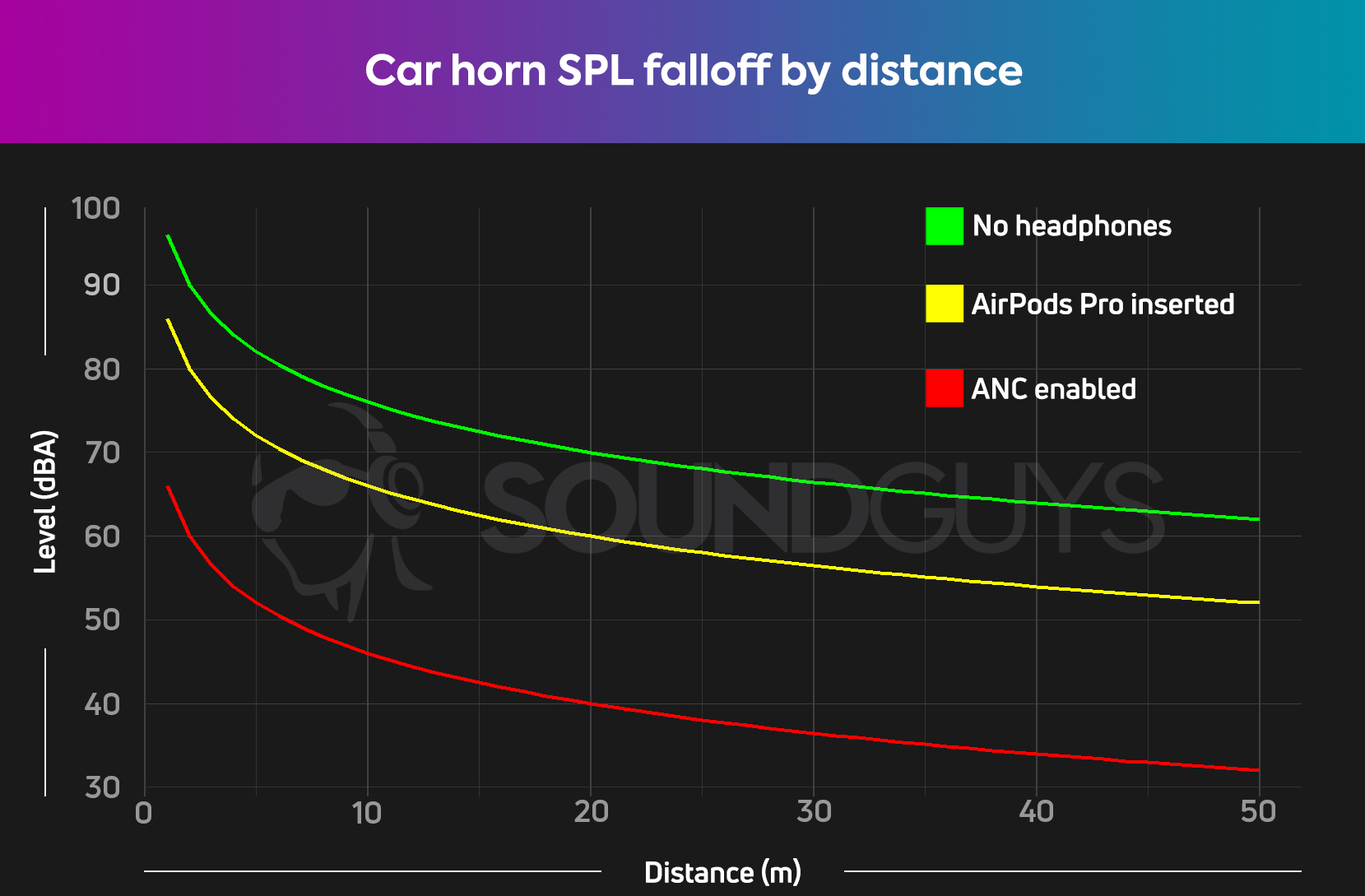

Anything that increases perception distance will increase your overall stopping distance—and that’s something you want to minimize. On the highway, you’re fighting not only your own brain’s propensity to filter out unwanted sensory data, but also the inverse square law. For every doubling of distance, a noise that comes from a singular point source will drop by 6dB, so the farther away something is, the quieter it will be. However, that causes a problem for emergency vehicles and car horns: there are often limits to how loud they can be to avoid giving their operators hearing damage—so it’s usually up to a driver to make sure that they can react in a situation where these cues are present. It’s why emergency vehicles have flashing lights to provide as many sensory cues as possible for other drivers to notice them, but if it’s broad daylight you may not see these as easily.

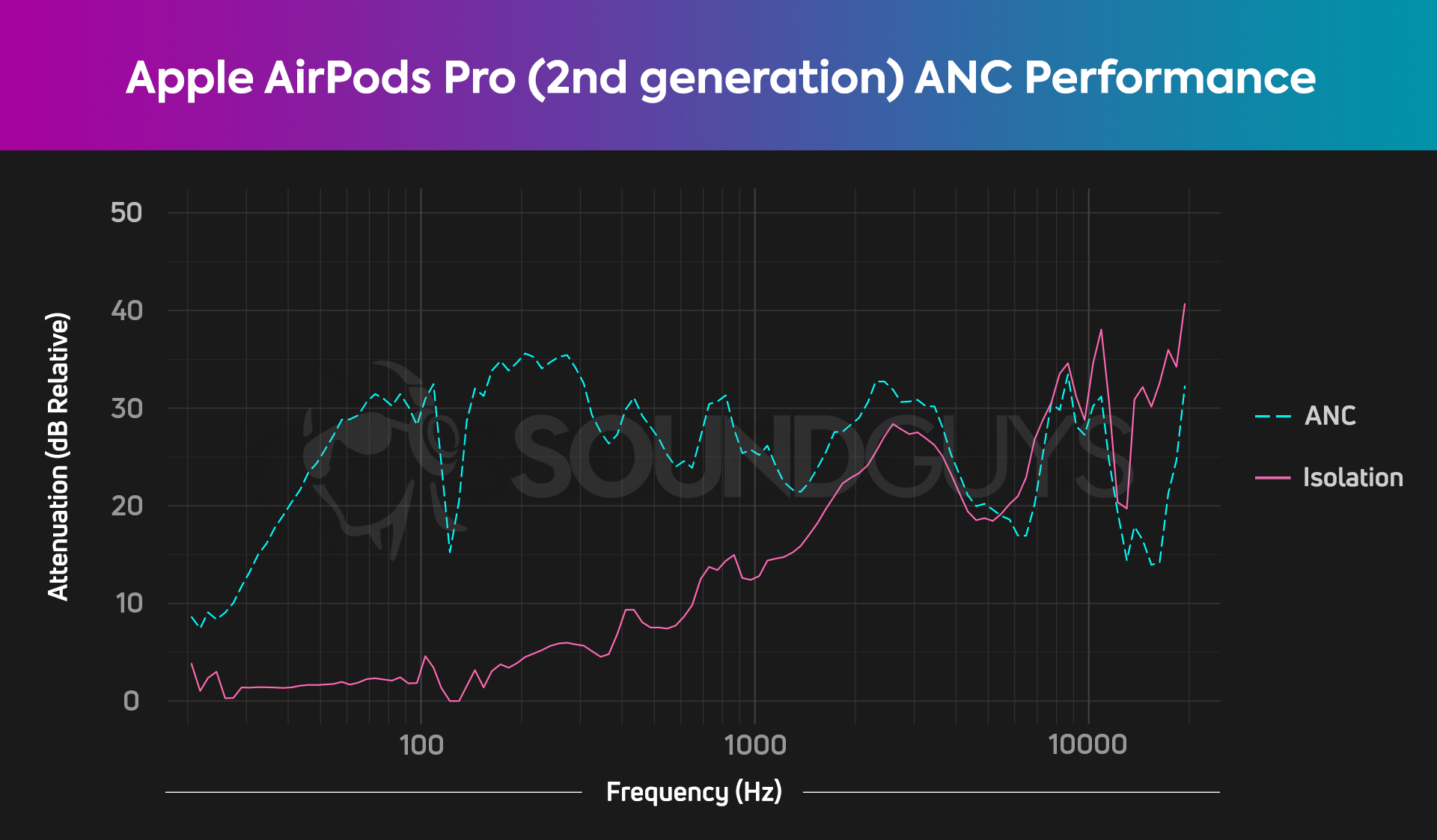

When you don’t have anything on your ears and you’re listening to the car radio, it’s a little tough to hear things like car horns at a distance, but in general you’ll be able to hear them because the music isn’t that much louder than the auditory cue. When you put any active noise canceling (ANC) or isolating products on your head, they will do what they’re supposed to do and make outside noise far quieter. In isolation this isn’t necessarily a bad thing, because the headphones or earphones affect each noise in a similar way: both the road noise and any sirens or car horns will be reduced in volume in a similar amount.

Considering the most typical center frequencies for car horns are around 420 and 500Hz, you can follow along on the chart above to see how the AirPods Pro physically prevent that particular frequency from reaching your ear (pink line). Even though sounds are complex signals and a single figure is not going to give you a perfect idea of attenuation, I want you to look at the pink line a little bit closer. The higher the frequencies are, the better the earbuds are at blocking them out even without ANC—meaning that overtones and harmonics will be tamped down as well, reducing the auditory information reaching your brain. That means that when you wear earbuds like the AirPods Pro while driving—even with the ANC off—the earbuds are going to reduce that car horn’s (420 and 500Hz) loudness by roughly half (6-10dB) at your ears. With noise canceling on, that figure jumps up dramatically the lower the frequency is—meaning sounds like truck engine noises will be blocked out by up to 87.5%.

The problem arises when you listen to music with headphones or earphones. Cues like car horns or sirens will be much quieter by the time they reach your ear while using these products, but your music will be far louder in comparison. To provide some context, we use a listening level of 75dB in our battery tests to simulate what a normal person would use for their headphones, and you’d listen in a car at roughly the same loudness—maybe a little louder—even if you aren’t blasting your tunes. If you’re wearing ANC headphones or earbuds and listening to music, a siren or horn that you could notice at 20 meters without headphones may not be audible (up to 8 times quieter). Music isn’t constant in its intensity, but the louder you listen, the harder it will be to pick out competing sounds that aren’t constant tones—especially when they’re much quieter than your music.

What about motorcycles?

Laws surrounding motorcycles are often the same laws that govern cars, but not always. In general there come carveouts for things like in-helmet systems (provided they don’t make contact with your ear) and hearing protection that would allow you to hear emergency vehicles. Only in Hawaii and Michigan are the laws more stringent for motorcycles, with Hawaii having a defined line against the use of headphones for motorcyclists, and Michigan having a law for bicyclists that could apply to motorcycles.

It’s less clear that a motorcycle will have all the same issues with headphones as a car, however, because the engine noise is usually super high—and anyone riding a bike has much greater visibility than someone in a car. Additionally, cycles tend to be much more maneuverable than cars, even if their braking distances are longer. So while the equation stays the same for stopping distance, the parameters are quite different when it comes to personal safety. We still don’t recommend listening to music over headphones on motorcycles, but as the act of riding a motorcycle is already operating with some reduced ability to perceive auditory cues (and a lack of data supporting it being a problem), we’re not going to take a stance on it either.