All products featured are independently chosen by us. However, SoundGuys may receive a commission on orders placed through its retail links. See our ethics statement.

Headphone burn-in isn't real

July 22, 2024

Even though I’m supposed to keep you reading for as long as I can, if you just clicked this link and internalized the title, you’ve absorbed everything you need to know. Seriously. Burn-in isn’t a concern for new headphones.

This is probably one of the most popular audio myths of all time, so a large segment of audiophiles will swear up and down that this is a make-or-break part of the headphone experience. It’s not, but like any good myth, it’s centered around a kernel of truth. A teeny, tiny, almost imperceptible kernel of truth.

So far, all the tests performed by various online outlets haven’t yet found objective data to support the idea that headphone guts actually change audibly over certain periods. Many manufacturers won’t comment on this phenomenon; if they do, they shy away from telling audiophiles that they’re wrong.

Editor’s note: this article was updated on July 22, 2024, to provide an updated example for data.

The “burn-in” myth

The popular belief that you need to “burn-in” a set of headphones or in-ears with hours of loud sample sounds like pink noise before they sound the best is just that: a myth. The myth states that the component that needs breaking in is the headphone’s speaker drivers. The idea is pretty straightforward — the materials headphones are made of will lose their rigidity over time as they’re subjected to repeated force and sustained heat. Such a loss of rigidity allegedly makes it easier for the speaker element to move faster, resulting in better performance.

Now, that’s almost true: your headphones’ drivers and housings will lose rigidity over time, but it won’t cause an audible change in the measured performance of the headphones — at least, not for the better. Larger loudspeaker drivers see larger amounts of material change over time, specifically in the surroundings, the part subjected to most of the flexing action. This area of the transducer is quite different in headphone drivers, and the amount of everyday use it would take to affect sound quality in a measurable way for headphone drivers is ridiculous. In fact, much of the objective “evidence” for this phenomenon is shown on charts with a scale of 1dB or less (i.e., insignificant).

The concept of “burning in” speakers stems from a simple quality assurance test performed by manufacturers where they drive speaker components for hours to see if they hold up under sustained use. The idea is that if the performance changes or degrades significantly during that period, the product quality needs to be improved. That makes sense — they do this for cars, cameras, and other machines, so why not headphones?

A change in sound that’s dramatic enough for you to hear would be cause for concern. If your headphones change in sound over a short period, like 50 hours, do the materials magically stop losing rigidity? Nope. A loss of rigidity in speaker materials would also mean the speaker would take longer to stop moving. That would result in degraded impulse response and ringing. This “burn-in” theory doesn’t make a lot of sense — even less so for in-ears, though there are many people searching for “in-ear burn-in.”

An expert opinion

My hunch regarding burn-in improving audio is twofold:

- Because we tend to believe what our friends tell us, confirmation bias is at work here

- The fit of most headphones changes over time.

To the first point, it’s an argument that’s been hashed out to death. However, even if you control for confirmation bias, some users still report an improved sound after a certain listening period. I’m very annoyed that this is often counted as evidence of burn-in because the second point is almost never addressed.

If I sound like a crank, I am — but you should listen to me. For those who don’t know, I tested audio products for USAToday for over five years. I used a Type 4128-C Head and Torso simulator, state-of-the-art measurement hardware, and industry-standard audio analysis software. I logged thousands of hours testing headphones on that fixture and learned a lot about the nature of objectively testing audio at that time. Today, in 2024, I’m continuing a similar battery of testing on the 4128-C’s successor, the 5128.

Headphones require a seal in order to perform their best, and a poor fit will wreck bass reproduction and increase noise and leakage.

When we test headphones here at SoundGuys, what causes us the most grief, annoyance, and botched tests is how even slight variations in fit alter what reaches your ears to a gigantic degree. It’s pretty incredible, really. Headphones and earphones require a seal in order to perform their best, and a poor fit will wreck bass reproduction and reduce isolation. When we test headphones that don’t fit correctly because the foam is too stiff — and therefore wouldn’t conform to the head — the measurements suffer immensely. I hate testing on-ear headphones because it’s unbelievably difficult to get good data without long periods of trial and error. With this in mind, let me paint you a picture of what might be happening here.

Ear pads are less durable than you think

While it seems like an obvious thing to say that the fit changes after use, that’s the main reason why so many on-ear and over-ear headphones appear to “burn-in.” Think of it this way: foam, fabric, and plastic are easier to deform than metal, right? So, why is it so incredible to believe that a set of headphones finally contorting its padding to your head and creating a better seal is the culprit behind headphones sounding better instead of burn-in?

Ever put a butt-print in your couch that doesn't go away because you sit in it every day? This is exactly the same thing.

The reason is that the cushion material in most headphone ear pads is a form of viscoelastic foam. Viscoelastic foam has a fun property called “relaxation,” where, over time, it becomes less and less able to hold its original shape or resist force than it used to. Ever put a butt-print in your couch that doesn’t go away because you sit on it every day? This is exactly the same thing. Relaxation can be accelerated by heat and is one of the reasons memory foam mattresses get less firm the warmer they are. This happens faster with cheaper padding like what’s in your headphones.

A set of headphones with relaxed ear pads will fit your head better simply because it will conform better to your noggin’s natural contours. A better fit means a better seal, and not only will isolation be far greater, but the headphones will sound much better, too — headphone responses are tuned with the expectation of a proper acoustic seal. Given that most of the hours I spent testing were wasted on trying to get a good fit on that damned dummy head: a good fit is the most important thing when it comes to headphones.

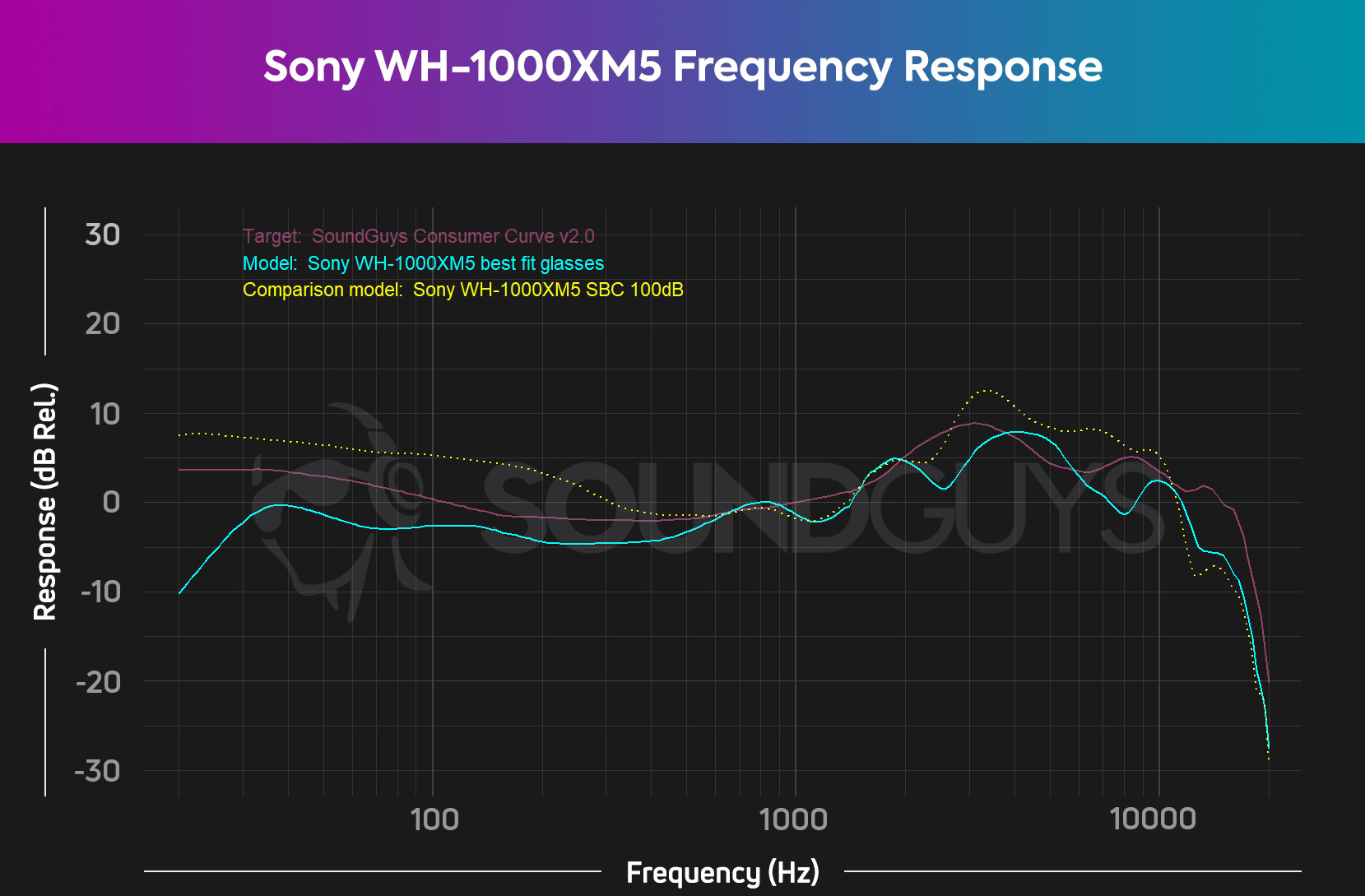

I don’t expect you to just blindly trust me, so take this example. We dusted off the Sony WH-1000XM5 we bought for review way back when and re-tested them. First, with a normal fit, and then we attempted to get the best measurement possible when the test head wore my glasses. Let’s see what happens when the variable of glasses causes your headphones to have an imperfect seal in the exact same position.

Yikes. That imperfect fit dropped those bass notes by about 10dB below their original reading. To your ears, bass will sound half as loud as it would with a perfect fit. That’s a huge, super-noticeable change in audio quality. While the changes in ear pads from brand new to broken-in won’t be this dramatic in most cases, it’s definitely something that could alter your listening experience — because it measurably does. Remember, it only takes a tiny air leak to compromise the seal.

Looking at the chart above, you can see the difference clearly. Keep in mind, this isn’t even an extreme example, just a common one. Over time, the viscoelastic foam will stop resisting so much against the glasses and your head, bringing the sound ever closer to that control reading. The more you use your headphones, the better they’ll sound. This is a much larger difference in sound than 1dB here or there by alleged burn-in advocates.

Your brain plays tricks on you

Even if you have perfectly consistent ear pads, it’s also a documented phenomenon that your brain will train you to prefer what sound system you’re listening to over time. In short, you get used to it the more you listen. While that doesn’t mean you won’t be able to find something you like better if you look for it, chances are good that if a set of expensive headphones doesn’t knock your socks off right away, it will take some time.

Now, if there’s a ringing or noise or any other audible artifact causing you pain or ruining your music, definitely return your headphones. But if the sound is most of the way there and not too far off from what you want, you may find that minor quibbles disappear over time. This is especially true with headphones that measure very well. Additionally, with headphones that are more or less “neutral,” there’s always the possibility of equalizing them to suit your tastes, so don’t sleep on the frequency response charts we post in most reviews. These plots will help you understand what you’re listening to and what changes you may want to make.

What you should do

Instead of burning in your headphones by playing pink noise on repeat for 50 hours, just start using them like a normal person. Burn-in is pseudoscientific at best, and breaking in your ear pads will have a much more pronounced effect on your music — and the only way to do that is to use your headphones.

You bought those headphones to enjoy, so go do it already!