All products featured are independently chosen by us. However, SoundGuys may receive a commission on orders placed through its retail links. See our ethics statement.

This absurd record player reminded me what music is all about.

May 22, 2025

At SoundGuys, the process of writing or filming a product review is deeply experiential. As journalists, what’s most important is first to centre ourselves on the experience of a given product, so we can give our readers insights and impressions that are authentic, human, and, above all, truthful.

And in the spirit of this truth, I must admit that this process is challenging. One often gets lost in the deluge of new products, from brand-new headphones to the latest true wireless earbuds somehow always claiming ‘the best’ or ‘next-gen’ ANC. After a while, it all blurs together: identical drivers, minor codec updates, manufacturers promising customizations that feel more like check-boxes than meaningful features. In tech today, it feels that innovation has plateaued. Like the law of diminishing returns, it seems the longer we find ourselves in this iterative cycle, the harder it is to arrive at an insight that is wholly, radically, dangerously authentic. Far from the technological wonder we witnessed in the early noughts, when the internet began to take the world by storm, the industry now seems buried beneath a sea of shallow upgrades, conspicuous consumption, technological stagnation.

I can’t help but feel we’ve lost some sense of what it means to create. The sheer wonder of experiencing a piece of technology that didn’t just promise convenience or novelty but offered a way of seeing, hearing, or being in the world that was new and original. It seems the only things really captivating to us now are products that appeal to nostalgia – technologies that were once great and that we’ve had to revive again because, perhaps, we lack that same audacity, that same spirit of risk that once drove generations to create above and beyond themselves.

Licensed nostalgia.

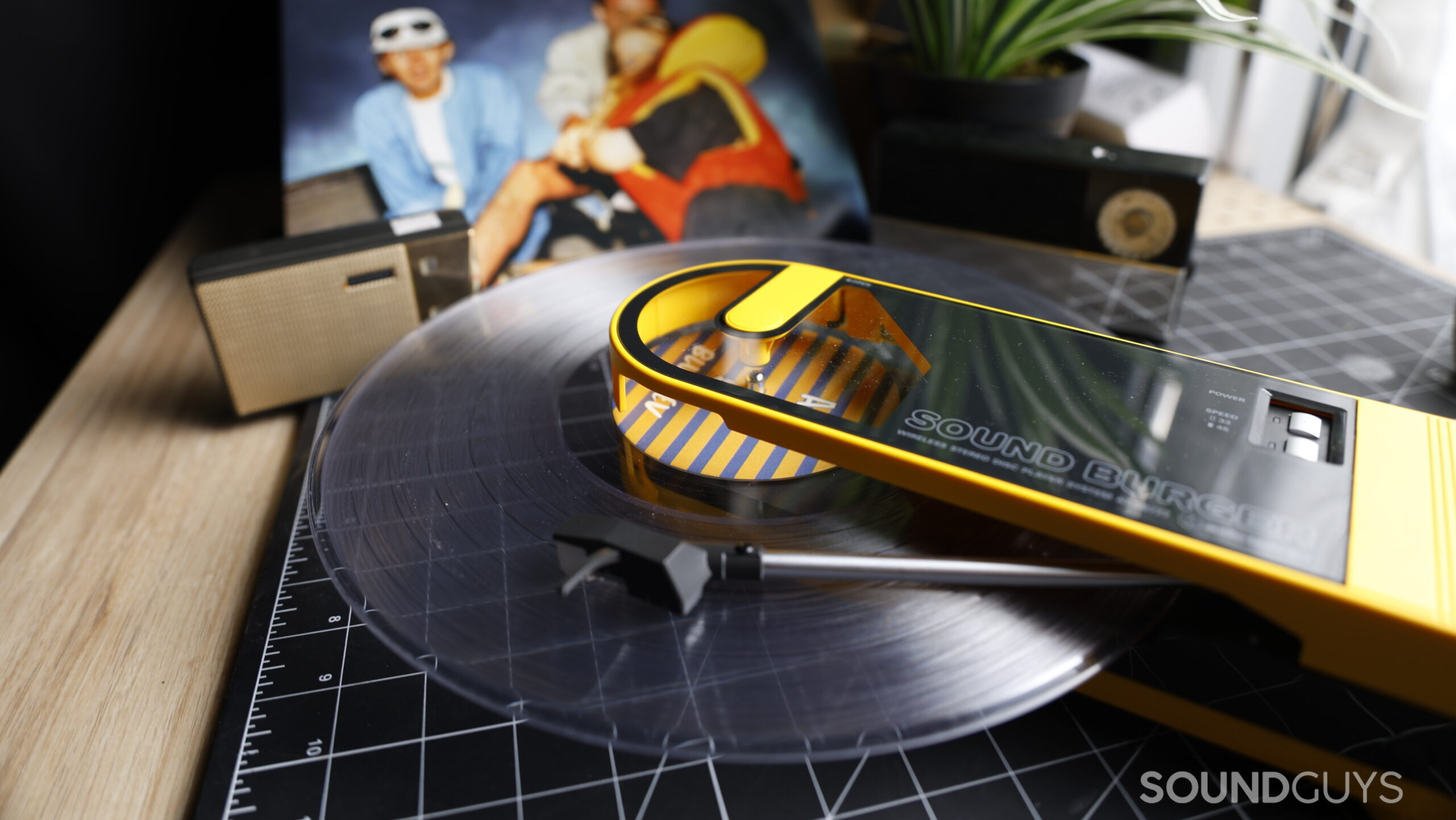

So, you can imagine my surprise when it was precisely one of these products that started to change my mind. This week, I’ve been spending some time with the Audio-Technica AT-SB727, also known as the Sound Burger. It’s a portable record player with a 12-hour internal battery that’s also packed with a host of modern features, like Bluetooth capabilities. By all metrics, the Sound Burger embodies precisely the kind of technological ambivalence and malaise I’ve been feeling about the industry. It’s a revived version of the original Sound Burger that Audio-Technica had put out in the 80s – in fact this particular Sound Burger I’m reviewing is a copy of a copy, a re-release of the gimmicky one-off Audio-Technica released for their 60th anniversary.

And gimmick is precisely the word for it – because I see little functional use, today, for a portable record player. It’s an absurd product. The thing skips when you jump a little too hard, let alone when you try to use it as a portable audio device. And if you thought CDs were tough to carry around in that little folder, imagine hauling crates of records around with you everywhere you go.

Imperfect media, perfect presence.

Yet last night, after a long day of shooting, I returned home and plugged my Audio-Technica ATH-M50xs into the Sound Burger’s line-out port, and reached for the nearest record in my record crate, which happened to be New Order’s Low-Life. And I sat there with my eyes closed, listening to that warm, crackly sound, and I wondered why vinyl has become this source of refuge for me from this technological deluge.

The vinyl industry itself has been the source of plenty of shallow nostalgic nonsense, trying to sell this antiquated, fragile, absurd sound technology to snobby hipsters (like me, truthfully) without having to innovate or push the bounds of what we’re really able to create.

And yet, I take comfort in the vinyl experience precisely for its imperfections, emphasized by the Sound Burger’s lack of a weighted tonearm or any of the more premium features of a tabletop setup. The crackles, the pops, the ‘wows,’ and the tone shifts all, for me, signal a kind of authenticity that’s still missing in digital audio, even if digital promises a more ‘perfect’ sound. The experience of digging through my record bin and literally holding my favourite artists’ creation in my hands — something that existed once only in their mind now embossed, by some technological miracle, in a plastic article I can touch and feel, whose cover art I can display, whose liner notes I can read, imagining myself in the studio watching their art unfold for the very first time.

And talk about watching art, because every time you put a record on the player, those layered sounds are reproduced then, in real time, by a needle travelling over a bunch of grooves. No matter how many articles I read, it still amazes me that such sonic depth comes from a diamond-tipped needle running along plastic grooves. By some miracle, I get to experience this art in its barest essence: as the communication of authentic feeling from the artist to the listener centered on active experience, active performance.

Why we still write about tech.

Weirdly, while listening on this less-than-ideal listening setup, I felt, again, that sense of wonder I once sought in continual possibility, continual creation, continuous progress. I saw it here, in this antiquated, gimmicky technology that just refuses to die in an age of algorithmic verisimilitude, where it seems we’ve started to lose the human side of music. As the record on my coffee table spun to its last few tracks, I closed my eyes and let New Order’s synthesizers drown me in their waves of sound.

Indeed, their synths create this total sound. They’re enveloping, all-encompassing, they wrap themselves around you. It’s not a hug, not an embrace. It’s a nuclear bomb. It fries your skin from the inside out, surrounds you in the immensity of its apocalyptic plume. One can’t help but admire the spectacle, can’t help but be struck by the sheer awe of what we were able and willing to do to rob ourselves of life wholeheartedly, viscerally, totally. To think that we are capable of such destruction, and simultaneously, capable of such life, should we choose it, should we hope that we use our abilities to create on a precipice of wonder, that same precipice I feel every single day in the large and the small, in totality and specificity, in freedom and brotherhood — it’s all too much: too beautiful, too fast, too violent, too strange.

And yet I choose it still, this life, in its radical defiance, its revolutionary promise: the seditious beauty and terror of the impossibility of being alive. That, there, is why we still write about tech, even in our age of stagnation. Because at its best, it reminds us of what it means to create, to be astonished by the world we’ve built.

Truth in imperfection.

Listening to these synths, even on an absurdly gimmicky record player, reminded me of the value of total immersion. It’s the kind of detail that showed me why people still romanticize analogue warmth even in a digital world. This longing for presence is why, I think, folks seem to be returning to older, more imperfect technologies. In 2024, for the first time in 20 years, physical music sales saw a year-over-year increase. Vinyl continues to be the top-selling physical music format, while cassette sales were also up 204.7% in Q1 of 2025 – out of a longing for something real, original, some semblance, perhaps, of truth.

And as a journalist, here at SoundGuys, that’s what I’m really chasing when I sit down to write a review. Not just signal-to-noise ratios or Bluetooth Multipoint performance — though those things matter — but moments like this. Moments where the product in front of me, no matter how absurd or obsolescent, suddenly reveals something deeper about how we experience music, memory, and meaning. These moments are why we still do this, why we still write about technologies, why, despite the plateaus and the stagnation, we still seek some kind of transcendental technological awe in new products. Because we know what it’s like to stand on that precipice of creation and innovation, and even then to look back and find wonder in even the most absurd and whimsical of technologies.

The best gear doesn’t just sound good. It makes you miss your bus because you wanted to hear the bridge of that song one more time. It makes you text a friend just to say ‘you have to hear this.’ That’s what we ought to try and chase with every review – that flicker of emotional resonance.

The Audio-Technica Sound Burger isn’t a marvel of engineering. It doesn’t compete with your high-end turntable, and it wasn’t built to. It wobbles slightly, the tonearm skips if you breathe too hard, and its appeal is almost entirely emotional. But in a world where so many tech products strive to be invisible, it’s the flawed, tactile ones that remind us we’re still here.

The Sound Burger won’t replace your digital setup, and it certainly won’t impress your audiophile friends. But it just might reconnect you with the reason you fell in love with music in the first place. With the kind of experience that doesn’t just pass through your ears, but roots itself somewhere deeper. A crackle. A synth swell. A moment of feeling that you didn’t see coming.

And if a portable record player from the 1980s, resurrected and reissued for no reason other than delight, can still do that, then maybe the industry isn’t done surprising us, after all.

Thank you for being part of our community. Read our Comment Policy before posting.