All products featured are independently chosen by us. However, SoundGuys may receive a commission on orders placed through its retail links. See our ethics statement.

Burn-in still isn't real

August 20, 2024

Audiophile myths tend to survive long after they’ve been thoroughly debunked, and I’ve been seeing claims of burn-in being a thing again. So, I figured showing more work would help us understand exactly what’s going on to get people to enjoy their headphones rather than perform some bizarre and unnecessary ritual before doing so.

The gut check

After reading several claims that burn-in is necessary again, I decided to test what I posited in my earlier article: I believe that the measurable effects of “burn-in” is most likely the ear pads relaxing and better forming to your head. I grabbed a couple of sets of headphones with very similar characteristics from the same company, which a product rep told me needed burn-in, though the manufacturer no longer overtly supports those claims.

For each set of headphones, I placed it on the test head, which is a reasonable analog for a human head outside of the temperature difference. I then set a sequence to blast high-level pink noise, punctuated by periods where we could record frequency response data at regular intervals over 24 hours. After each round, we could compare how the headphones’ sound changed over time.

By comparing these sets of measurements, we can now get a good idea of what changes are burn-in and what could probably be attributed to the relaxing padding. After completing each round, I archived the data for future use and continued.

I should point out that previous attempts to measure burn-in were largely performed on test heads and fixtures that were a little more friendly to getting a perfect seal every time. That’s a problem for us because human heads aren’t often as flat as these test fixtures are: we have jaws, and weird bumps on our skulls, and hair. If it does turn out that the pads are the culprit behind the impression that burn-in is real, then it might be possible that the differences people are noting are more significant than the ones we’ve found here, as they weren’t getting a good seal to begin with. If that improved over time, it would be easy to see how that could be misconstrued as “burn-in.”

What we recorded

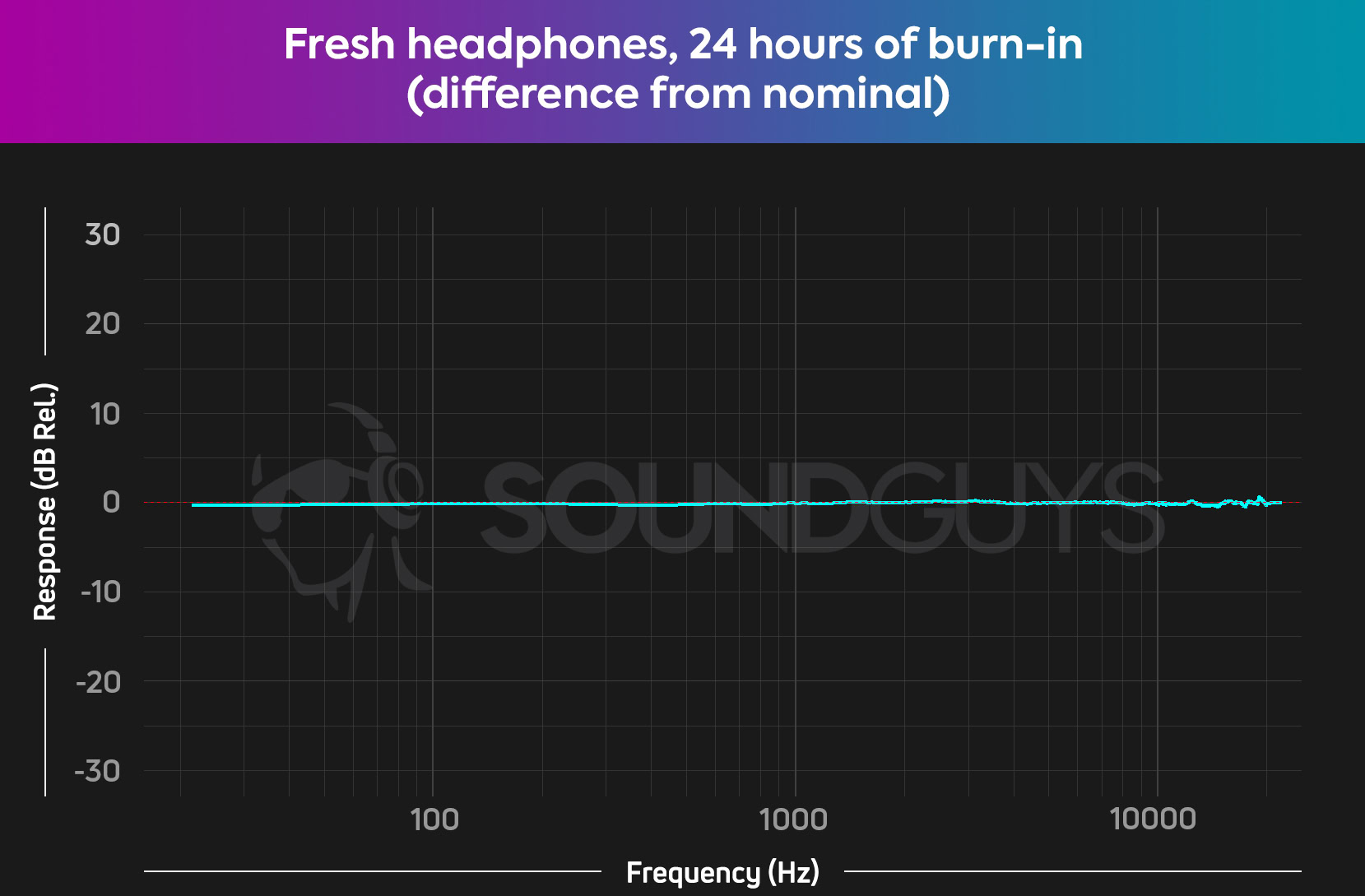

Rather than posting the raw measurements, I will show how the sound changes over time by subtracting the first measurement from the comparison data collection. That way, we’re only looking at the difference. Anything above 0dB is an increase in level, while anything below is a decrease in level. I’m doing this so we can see how things change more easily, because people generally have a tough time reading multiple lines on a chart. Let’s take a look at our set of headphones that have been burning in on the head for 24 hours. This model should show the most drift from its nominal performance, but we can break this down hour-by-hour if we find significant differences.

Not much here, but that’s not unexpected. Other data collections in this vein showed similarly small changes, and there’s no reason to believe we’ll run into anything super drastic here either.

If you were to zoom in on the line to an absolutely ridiculous degree, we can see a slight lift in the bass and mids, and the highest highs start to vary a bit. Presumably, the bass bump is due to a better seal, and the variances in the mids and highs are because of the distance between the source of the sound (the driver) moving ever-so-slightly over time, and interacting with the ear differently. It’s worth noting that the measurement shows a louder average signal than the initial collection — you know, something you’d expect from an improved seal. But, the scale we need to zoom in on to even see it on a chart is… unreasonable.

As this should theoretically be our high water mark for both burn-in and pad relaxation, it’s doubtful that we’ll be able to draw many conclusions from our hour-by-hour data. When the signal remains +/- 0.25dB until about 8.5kHz, you’re really stretching to make a mountain out of a molehill if you think headphone burn-in is real.

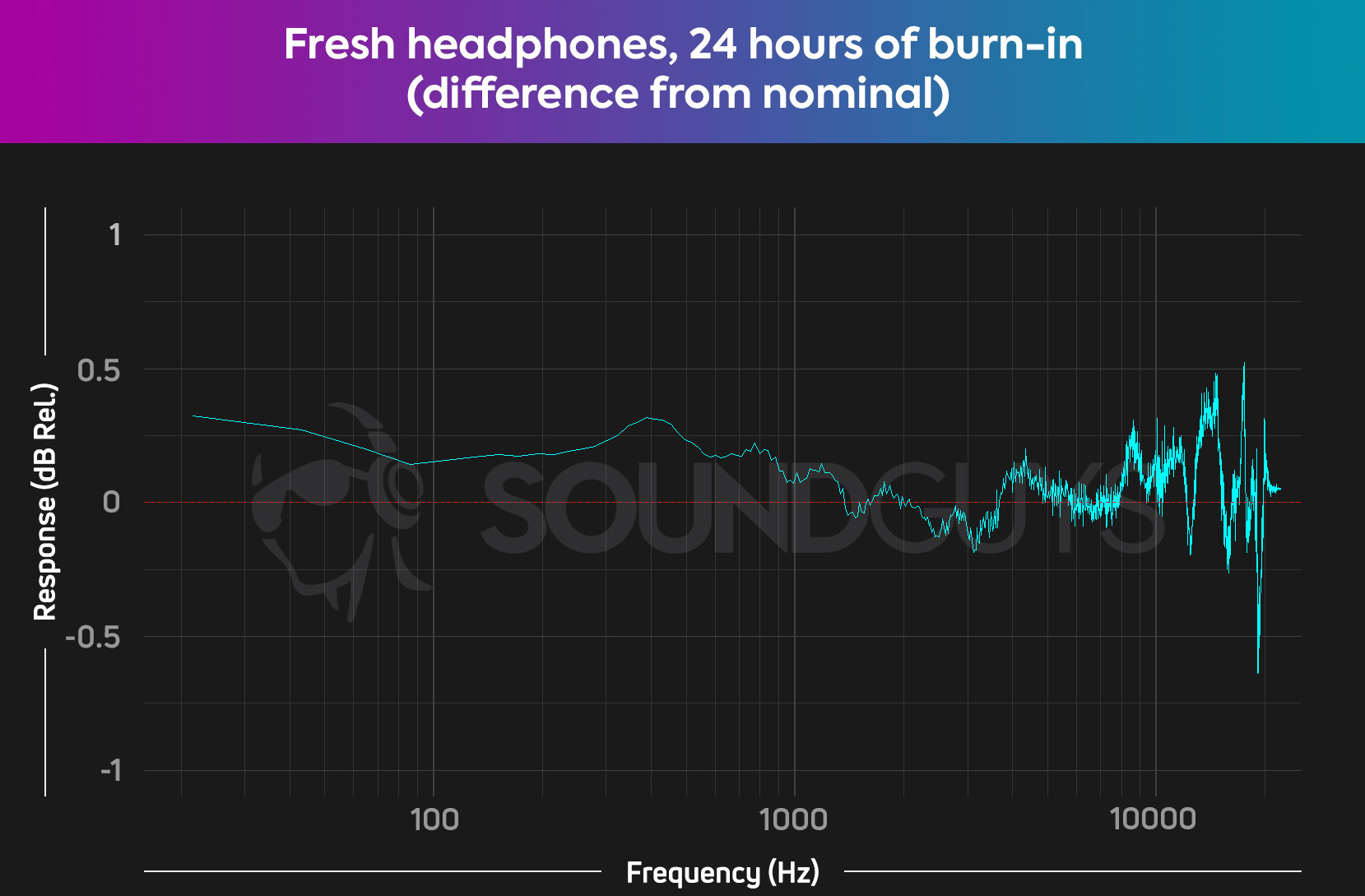

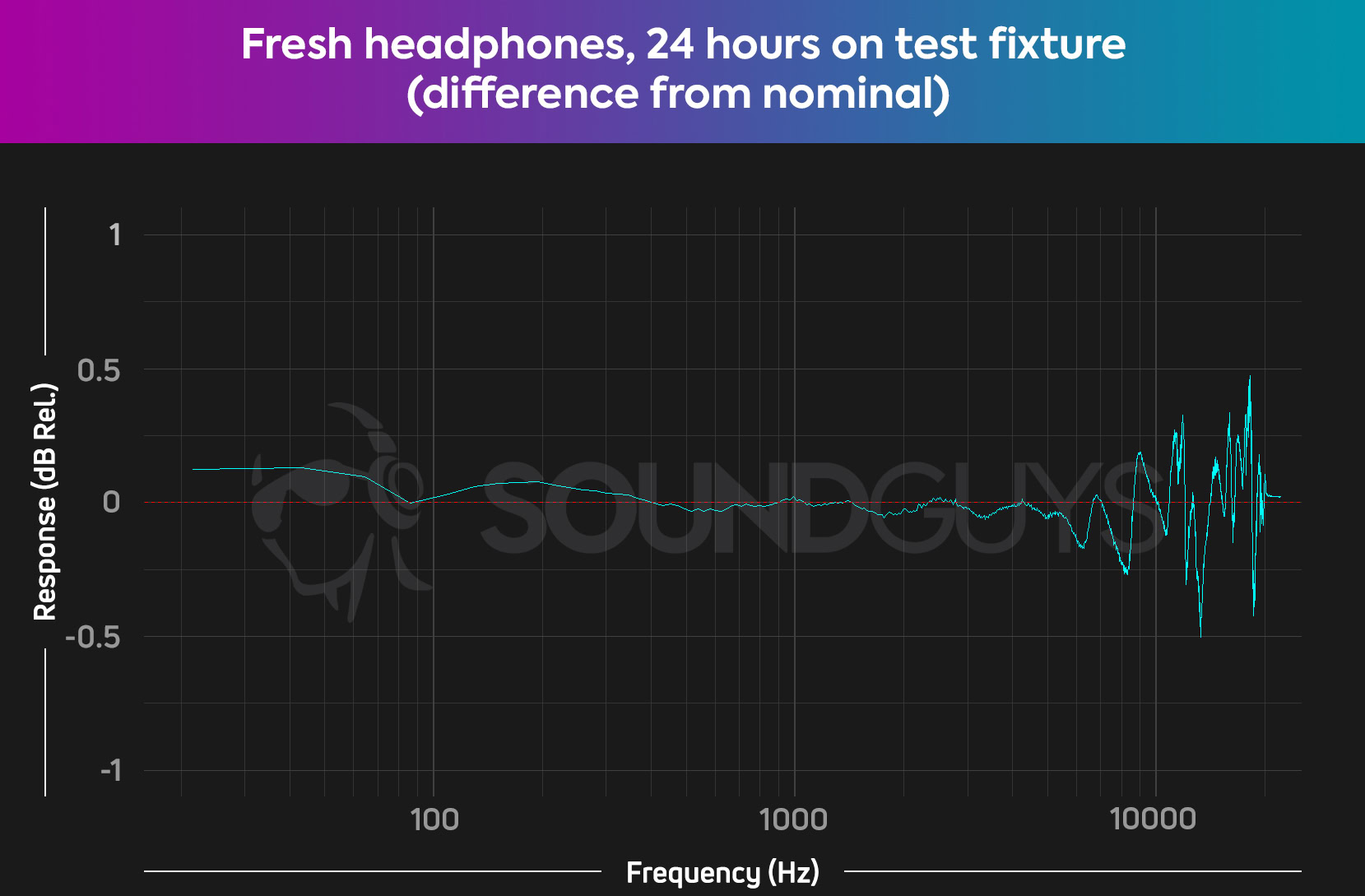

What I didn’t tell you is that I put my proverbial thumb on the scale here, as the headphones I chose for this are very heavy (over 500g), so the pads should have relaxed quite far. I did this because I wanted a “worst-case scenario” to see how much a set of headphones could drift. If we were to drop the mass of our device under test by about half, we get something that looks like this:

Huh, that’s weird. It looks a lot like the first chart. Sure, the degree of change isn’t the same, but I suspect that’s because this set of headphones is a fair bit lighter than the first one — ergo, less clamping force on the pads. I’ll go out on a limb and say that this makes it seem like changes in long-term listening are mostly due to psychoacoustics and pad wear — not “burn-in.”

Where does this leave us?

If someone tells you that you need to burn in your headphones, it’s probably a safe bet that you don’t really need to. The process of “burning in” should involve you listening to your music like normal and allowing the pads to break in, instead of waiting a certain number of hours while your headphones blast noise or signals in a drawer near the computer. While some manufacturers suggest continuing with a “break-in” or “burn-in” period, it does not make much of a measurable difference in my experience. If it did, that would be cause for concern.

Remember, the point of headphones is not the equipment itself, but what you use them for. Chasing perfection with poorly attested rituals doesn’t really help matters, but turning your brain off and enjoying the ride will.