All products featured are independently chosen by us. However, SoundGuys may receive a commission on orders placed through its retail links. See our ethics statement.

Podcast: Drones gone wild!

August 15, 2018

Check out the SoundGuys Podcast on iTunes! This episode “Drones Gone Wild!” can be downloaded here. Below is a full transcript of the podcast. Be sure to subscribe to iTunes for more episodes!

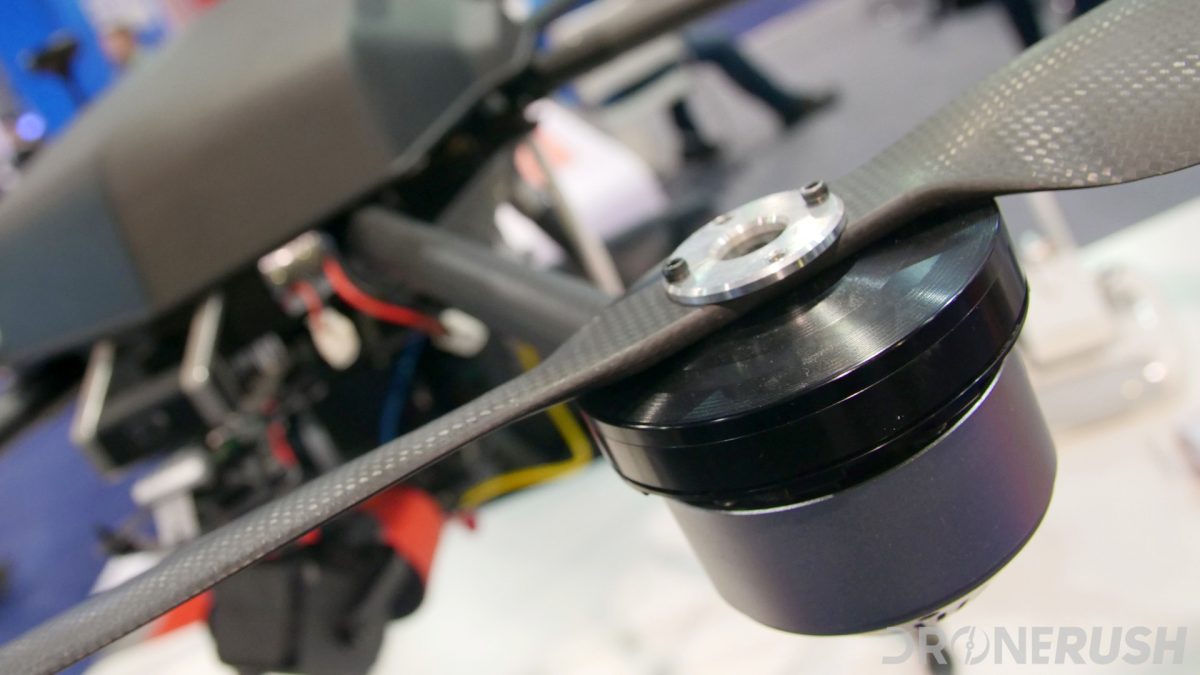

Image credits: Dronerush.com

Hello and welcome to the SoundGuys podcast. I’m Chris Thomas, Executive Editor of this publication, and I’m joined today by editors Adam Molina and Lily Katz. Also joining us today is Jonathan Feist, editor of dronerush.com as well as David Astorga, Airport Operations and UAS lead for the Oregon Department of Aviation—though for today’s purposes he’s representing himself, and not speaking on behalf of his organization. And today we’re talking about drones and their effect on local wildlife with their noise.

Similar to the internet, drones were initially developed for military use. In 1883, the first drone featured a rudimentary design: a camera strapped to a kite. It wasn’t until 1898, during the Spanish-American War, that one officially took flight under the U.S. military. Though drones are still used in the military, we’re here to discuss their more innocuous, pedestrian use: wildlife photography and videography. Let’s get into some of the pros and cons of using drones.

To start things off on a positive note, drones can be used to protect animals. Now, in 2014, BBC reported that drones were being used to combat Kenya’s poaching crisis. The drone company Airwave and the Kenyan reserve, Ol Pejeta Conservancy, teamed up for a 10-day study and found that drone technology is effective at catching poachers, especially since the night vision can collect much more light than our eyes.

In another instances, we may choose to study animals and a prime example is Planet Earth II. The crew was able to capture images of the Araguaia river dolphin, which is so rare that they’ve only ever officially been recorded by scientists once back in 2014. If we can learn more about wildlife, we may better understand how to cure diseases and treat illnesses. Also wildlife is just insanely cool.

Drones are used in many ways, from recreation, to law enforcement, to commercial inspection. But they all have one thing in common - noise.

Skylogic Research’s 2017 Drone Market Sector Report found that the most popular use-case for drones, is like Chris said, photography. Now, I agree that the documentation and study of animals is important. It just unfortunately still results in noise pollution. What’s more, the same report found that drones are used by law enforcement for search and rescue missions — and for scouting and recon. Though these are generally positive-use cases, they still manage to disrupt wildlife—even if it’s an unintended consequence. So what are some of the directly harmful uses of drones?

For one, let’s take bird strikes. This is when a bird collides with an aircraft like it sounds, and it’s a hazard that all aircraft are vulnerable to. This not only damages your drone but also causes premature death of an animal. Fortunately, the Federal Aviation Administration has a comprehensive procedure for reporting such incidents.

Noise affects animals in many ways – positive and negative

Additionally, drones that were released before mid-2017 were fairly large and produced excessive amounts of flight noise which can distress animals and indirectly result in their death…again. A report published in Nature Communications found that human-generated noises hinder an animal’s ability to evade prey. They found that the exposing the Ambon damselfish to motorboats decreased their reaction time, resulting the damselfish being twice as likely to be consumed by its predator. Talk about rough odds.

In the case of drones, propellers may mask an animal’s ability to hear its surroundings and lead – again – to premature death. To get a more comprehensive understanding of how this occurs, it’s important to understand how animals actually use sound.

Animals can often exhibit reactions to stimulus much like humans do. For example, there’s anecdotal evidence that cows produce 0.73 liters more milk when calmed by music… and even the goldfish can be trained to tell the difference between Bach and Stravinsky.

Much like humans, animals will be distracted by loud sounds they don’t understand what they are or where they’re coming from. When you’re lower on the food chain, this can lead to the fear of a big new predator coming to kill you. Like any being hearing their potential doom incoming, the fight or flight response kicks in, and puts enormous stress on the body. Animals are also able to hear far different ranges of sounds than humans can, so while a drone high up may sound a bit like a mosquito—or nothing at all—to you, it could be super loud for them. Loud enough that they can’t hunt, or find food properly.

Drones have been documented to do exactly this to foraging birds, small mammals, and bats. Even the mighty eagle reacts strongly to drone noise, as it can be seen on YouTube attacking and killing a drone near its roost. We even know that drone noise does result in increased heart rate, as you’d expect from a stressed and possibly mortality-preoccupied animal.

It may seem like one of those things that we as humans should just write off as something animals need to adjust to, but remember, anything we do to upset the balance of native populations of plants and animals has consequences down the road that we may not be able to foresee. If we scare a food source for predators away from an area, the hungry survivors will need other sources of food- and as an outdoorsman I’m not exactly keen on thinking about defending myself from a cougar or desperate bear.

Animals tend to gravitate towards places where humans don’t clear cut forests or otherwise destroy an existing habitat, and that usually means a national park in the US. But what happens when you make a stretch of land somewhere where the predators can’t hunt, and the prey don’t stick around? Animals move to a different place.

Interviews with Jonathan Feist and David Astorga

Jonathan Feist: They move to Canada. (laughter)

Adam Molina: What are the laws in Canada? Are they the same as in the US more or less?

Feist: On a national scale, the drone rules seem to have been fashioned after the FAA rules, yes, however, Canada does have one rule that the US does not and that is the complete prohibition of drone flight within 150 meters of wild animals.

Molina: Yeah, like if you’re in the middle of a forest, how can you tell exactly how close they are?

Feist: Well, if you’re in a national park, lets just say it’s a safe bet there’s an animal nearby. I fear that’s how the rules are going to go, “Here’s your no-flight areas.”

Thomas: I’d be interested to see if there was any sort of evidentiary-based law that comes out to temper this a bit. Because you got to wonder if all animals are affected the same way?

Feist: Now that harkens back a little bit to the FAA bird strike or animal strike reporting system that they have in place. I forget the exact number now, but I believe it was all animals above two pounds.

I fear that’s how the rules are going to go, “Here’s your no-flight areas.”

Lily Katz: You know, on a related note Feisty, when I was given the opportunity to talk to David Astorga who is the Airport Operations and UAS Lead for the Oregon Department of Aviation, he shared some insight on this. Full disclosure before we really dive into it, he represents himself, rather than the Oregon Department of Aviation for his contributions to our discussion.

David Astorga: The best position that any state can take on this or any municipality or local government at that, is treat drone laws as an accessory to already existing laws. Whether that be for wildlife protection, for hunting, angling, harassing wildlife, you view the UAS as an extension of current law.

Feist: From the FAA, there’s actually minimal laws in place that deal specifically with the animals. The one major law that they do have in place is flight rules protecting wildlife areas. This is protected airspace, where for the most part all aircraft have to be at least 2000 feet above the ground.

Now of course, for UAS or unmanned aerial systems as the FAA calls then (drones as the rest of us call them), the maximum altitude you’re allowed to fly is 400 feet. Which means, you’d never be able to fly in a protected wildlife area, which is great, you know, protects those animals. However, there’s a small exception to that rule. I mean, this is going to be a minuscule use case, and effectively will not bother the animals, however, let’s say there is a cell tower that measures 2000 feet tall—those do exist believe it or not—if it is within 400 feet of the edge of a protected wildlife area, a pilot could navigate from the ground up to the 2000 foot mark outside of the protected area, and then fly over the area.

Now I have to tell you, your basic, compact folding drones, by the time you get to 400 feet, it’s very difficult to hear that with the human ear, if at all. However, you can fly drones that weigh up to 55 pounds—I’m sorry, they have to be less than 55 pounds, but 54.9 pounds works. And a machine that large could produce the noise that could be heard at 2000 feet away.

So, I mentioned that the FAA has limited drone laws for animals themselves. That’s because they have handed that off to other factions of the government. So in the federal, state, and municipal levels, there are laws in place to protect humans and animals.

Laws and penalties

Astorga: We have a state preemption which reserves legislation related to UAS, for legislative assembly. What that does is it prevents a patchwork quilt over the state, so different counties, municipalities, and cities, there’s not different policies in place.

Katz: If someone violates any of these regulations, let’s say someone does fly over a state park where it’s not legal to, how are they able to track that drone back to the pilot?

Feist: I am glad you asked this, because it is very much the early days of drone law and drone registration or policing. To answer that properly, I have to specify one quick thing here: The FAA is the only entity that controls airspace. When the national parks and state parks say that you cannot fly the drones, what they are saying is that you cannot personally be on the property. If you launch the drone legally outside of the park, you can fly the drone over the park airspace.

The reason I’m glad you asked this question is how do you know who that pilot is, where that pilot is, and what kind of repercussions can you put in place on them? Right now, it’s fairly minimal.

Astorga: With the state, public agencies register with aviation, and then through statue, they are required to provide annual reports reflecting the type of mission, and a date. You have to figure out how you’re going to manage all that. So there’s a flight side, there’s a policy side and it all intertwines. In Oregon, we only register public agency drones. Those entities that have registered, provide us with annual reports. And a lot of the times, those annual reports develop into some kind of cost-benefit analysis. If that’s not provided to us that’s ok, because all my agency is looking for is mission and date.

Molina: Is there anything that the companies that manufacture these drones themselves are doing? When I was with you and you were flying a drone but you were saying that DJI was able to track the flights?

Feist: Correct! We’ll talk DJI of course, they’re the most popular retail drone manufacturer around. Every piece of data that they can collect on that drone telemetry is stored in a log for you to look at later. Now of course, you and i think of drones as you know, these toys machines we fly in the park, but to be honest, the major usage of drones is very rapidly expanding to commercial operations. We’ve all heard of like Amazon delivering packages and the like. What you may not have heard of is a little company called Insitu. They’re a Boeing company and they produce a number of military style fixed wing drones – some of these are used for the military – but a lot of them are being used in the United States over top of forest fires.

Drones are able to stay in the air for upwards of 24 hours, they fly at high elevations, and they’re helping manage these fires. As a small anecdote on that, I do have family who have helped with forest fires. When they are on the field, traditionally, they get paper maps hand delivered to them. Those maps had to be printed and they could be up to 12 hours old. And that can put lives in danger and certainly puts animals’ lives in danger as well.

Katz: How about for search and rescue?

Astorga: For search and rescue or whoever may use drones, I see it as a tool for them to really analyze how much they save, maybe a reduction in flight preparation, or a more efficient use of manpower or funding. There’s a lot that you can analyze. I’ve talked to different agencies around the state. A sheriff’s office out of Wheeler County. It’s in a rural area, mountainous terrain, and there are no airspace [conflicts]. They use their UAS for suicide prevention. Well, it’s not per se “prevention”. If they need to climb down a cliff line to check if someone had actually committed suicide, they really amplify their manpower by sending a UAS down to inspect surround cliff lines or any suspicious activity, rather than one sheriff climbing down, risking their life.

I’ve even gotten called from Alzheimer’s care facilities and they have a lot of – they’re not “runaways” I think they call them “walk aways”. If they can put up a drone just to see how far a patient has travelled, so they can get to them, that’d be real helpful.

Commercial Uses

Molina: What other uses are there for commercial drones besides that?

Feist: Primarily, we’re going to be looking at agricultural drones, railway inspection drones, power line inspection, and we have bridge inspection. Now bridge inspection I think is going to be one of the bigger animal incidents and interference items. Most bridges have birds around them, and they have animals that hide in the shade below, so these drones will be flown frequently, and these animals, I expect bird strikes, and I expect plenty of disturbance of animals below these bridges. And this is already a high-stress area, and a confined space under the bridge or overtop of the bridge if that’s how they’re going. So we’ve got a high-stress area that we’re gonna be adding extra propeller noise to.

Katz: Oh that actually reminds me. David had some relevant information that he shared with me about pre-established rules for protecting wildlife from noise.

Astorga: There are already protections in place regarding protection of wildlife for noise. For United States Fish and Wildlife, with whatever land they’re protecting in the state for whatever type of wildlife, there’s a permitting process for manned aircraft that want to operate in certain areas.In the State, let’s say an agency needs to fly a mission using a UAS, they go through the same permitting process as they would for a manned aircraft. And to protect nesting eagles, you have to go through this permitting process with the feds, and through that, that’s how you kind of mitigate noise and protect the airspace that’s surrounding whatever wildlife you’re trying to protect.

A quiet drone, is an efficient drone

Molina: Is there any attempt by companies to make quiet drones?

Feist: Oh, there certainly is, yes, and I urge all drone manufacturers to push forward with this because a quiet drone is an efficient drone. We’ll talk about DJI. In 2017, they introduced the DJI Mavic Pro Platinum. And as well, just here in May of 2018, they launched the Phantom 4 Pro version 2.0. On both of these drones, they introduced upgraded propellers. But more specifically, they’ve modified the ESCs – the electronic speed controllers. These are the devices that control the amount of electricity going to the motors themselves. And instead of an older-school clunky design, if you will, they’ve gone with a sinusoidal power flow. It produces much more efficiency, but reduces noise quite a bit.

And when we talk about the Mavic Pro, we’re talking about a four decibel reduction in noise from the regular Mavic Pro to the Mavic Pro platinum. That doesn’t sound like much, but four decibels is actually about a 60% noise reduction.

Katz: So I have a question. I actually, just before we recorded this podcast was out walking my dog, and people are a few houses down doing some lawn mowing and everything, and she was distressed. Have you seen that or experienced that domestic animals are also being affected by this, not just wildlife?

Feist: Oh absolutely. Also think about your vacuum cleaners inside the house. Obviously every animal is going to act differently to these noises, but in the case of this drone and let’s talk about dogs specifically, I have noticed that this is a huge hindrance at first. When they identify a noise, when they don’t know what’s happening, they do not look up. Dogs stick their nose to the ground, smelling around to trey and figure out what something is.

So what I have done, my own personal habit, is to condition the animals. If they all of a sudden have this loud drone flying above their head, they’re going to be terrified, presumably. So, the last time, I flew around a dog, I took the time to introduce the drone, powered off, just let the animal see what the drone is. Then I put the drone down, and “armed” it, we call it, when it’s sitting on the ground, but the propellers are spinning. Makes a little bit of noise, but it’s enough where the animal is like “Ok, what’s going on?”

And that is pretty much the key point in my experience where you yourself have to act calmly to show the animal that this is ok. And they’ll usually, hopefully follow suit. This is not to say that your animal is going to be completely calm with the drone. But at least you have eliminated that distress from not knowing what that noise is. Actually, if we’re going to continue on this, I’ve had multiple experiences with dogs and drones. At one point, I was flying near some bird-hunting dogs. It’s a very prey-heavy animal that is very excited to be able to chase down birds. It mistook my drone for a bird. In this particular case, unfortunately, stitches were needed.

Katz: Have you noticed that other pilots within the drone community are equally as concerned, or is that more of a rarity that you come across?

Feist: Neutral, to the honest. I’ve seen a number of drone pilots who, essentially are reckless and do not care. They’re just out there to have some fun. But I’ve also seen some pilots who have opted to carry their drones and use it as a handheld camera for fear of disturbing animals. And that hearkens back to the basics of science: to analyze something is to affect something. And that is very much true of drones, putting them in the air is to create noise.

Now that being said, once the drone is in the air, I have had a couple of experiences with hawks as well. Thankfully, these hawks have been curious, and not aggressive thus far. But perhaps that was because of my actions with the drone in the air. Both times, I had hawks come in from afar. They’d seen the drone, they came to check it out. I immediately landed the drone. That’s their airspace first. There’s no point in trying to hurt or harm and animal in the air. I got out of their way. There are birds around the globe, especially around airports, that have been trained as deterrent animals. These sorts of animals have been trained also to take out drones.

Final thoughts

Katz: Any sage wisdom that you want to share with us Feisty? David?

Feist: Pay attention to where you’re going to fly. Take the time, figure out where you’re going to go.

Astorga: Understand your boundaries in flight.

Feist: Is there a park nearby? Is there a protected animal preserve nearby?

Astorga: Know your surroundings. Your situational awareness is important to understand the airspace you’re operating in.

Feist: Think about how you’re flying. Stable, smooth, hovering operations are going to be the quietest. Remember that your legal drone altitude limit is 400 feet. And while you’re up there, keep in mind that birds do fly that high.

Astorga: And make sure you everything in place to operate in a compliant manner. That’s like the biggest thing. But having that safety culture in place, I think it’d be good for the growth of the industry.

Feist: Choose your elevation wisely.

Katz: Well, thank you again Feisty and David for joining us for our third podcast to discuss the impact of drones on wildlife.

Thomas: And that’s all for today from us here at SoundGuys. Thanks for listening. If you made it this far, you obviously like what you’re hearing. So please be sure to subscribe and share with your friends, family and even your dog if it like chasing drones. If you’d like to know more about the latest and greatest drones, be sure to check out Mr. Feist’s reviews on dronerush.com. And for all things audio, definitely come take a peek at SoundGuys.com. I’m Chris Thomas and from all of us here to you: happy listening!

Image credits: Dronerush.com