All products featured are independently chosen by us. However, SoundGuys may receive a commission on orders placed through its retail links. See our ethics statement.

Do you need an amp?

December 3, 2024

If you’ve developed an interest in what is known as “personal audio” and have already invested in a decent pair of headphones, it’s quite likely that you may have wondered about amplification. Specifically, what we’re talking about today is whether or not you will experience any appreciable benefit from using a dedicated headphone amp to drive your prized cans.

You only need an amplifier when your source’s maximum electrical output through the headphone jack—whether it’s a smartphone, laptop, or something else—is lower than what your headphones require to reach the output level you want. Bluetooth headphones will never need an amplifier, as the headphones themselves deliver the power to the drivers internally.

Editor’s note: this article was updated on December 3, 2024, to address more FAQs.

Why would you need a headphone amp?

If and only if you’re using wired headphones, plug them into whatever you’ll be listening to them with. Can you get the volume up to a good level? Is there room to spare?

If you answered “yes”, congratulations! You don’t need an amplifier. An amplifier’s job is to increase the power output of your source to the level you want, and if whatever you’re using to listen to music can do that on its own, a lack of power isn’t one of your issues. You can stop reading here and go enjoy your audio adventures! If your audio sounds bad, it’s due to something else.

If you answered “no,” buckle in; we’ve got some math to go over.

When you crank the volume on your smartphone but can’t reach an acceptable listening level, a few things could be happening.

- You’ve gone and done it: you cooked your ears, and now you’re hard of hearing

- Your headphones are broken

- Your source can’t satisfy the power requirements of the headphones

The first item on that list can’t be solved, but thankfully, it’s the least likely scenario. The solution to the third problem is an amplifier.

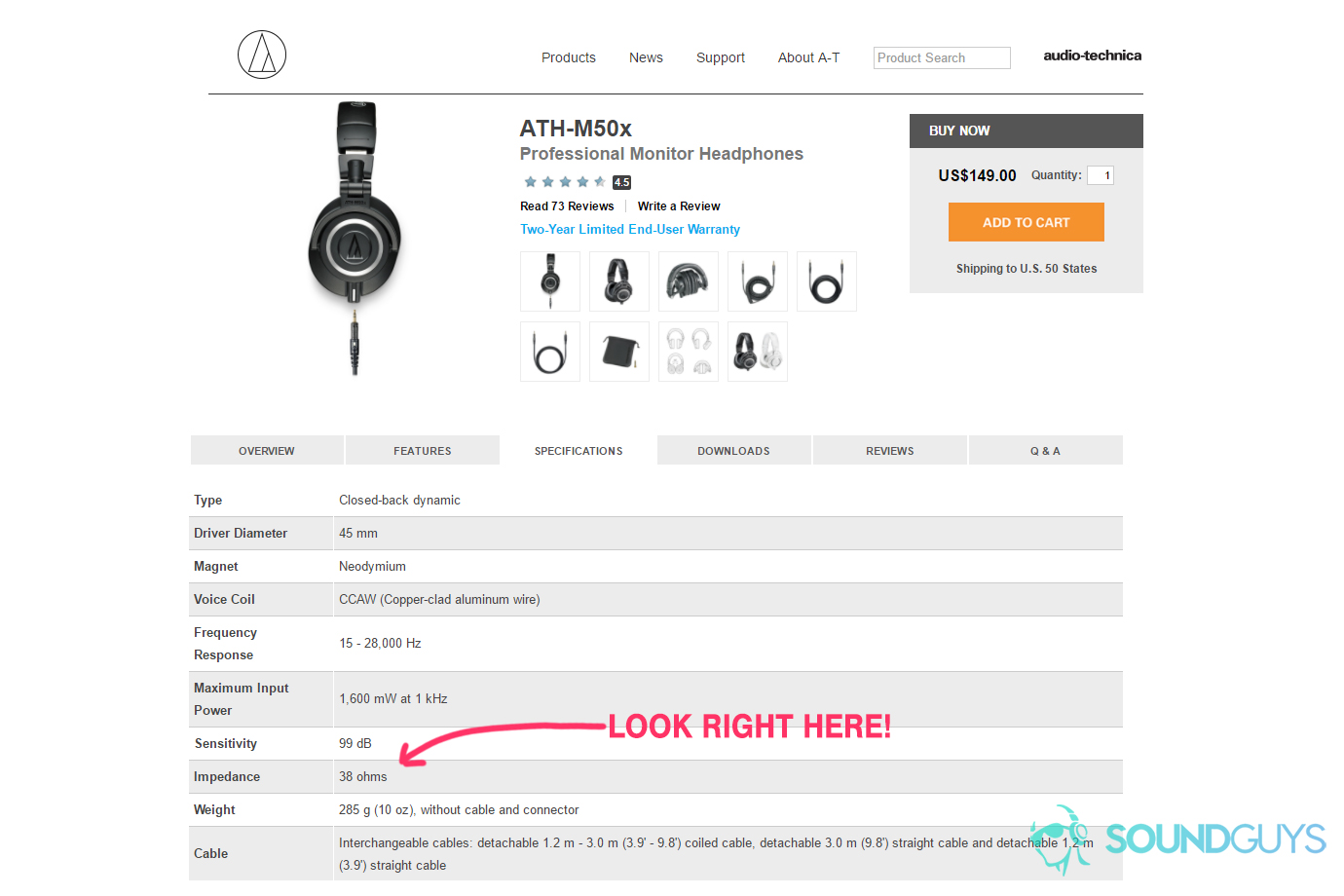

I need you to go to the specs page of whatever headphones you’ve got (or are planning to buy) and take down a couple of numbers for me. Got a pen and paper? Write down the impedance and the sensitivity of your cans. Impedance is the ability of your headphones to resist current, and sensitivity refers to how loud they’ll get with one milliwatt of power. If your eyes just glazed over, don’t worry: it’s not just you. This can be boring. All we’re doing here is just trying to figure out if whatever you’re using to play music can get whatever power the headphones you need to reach your normal listening volume.

These numbers will be able to definitively tell you whether or not you need an amp with your source, but it takes a little bit of math. If you’re unlike me (and you have a life), you could use this tool and be done with it… but wouldn’t you like to at least understand what’s going on?

Why were amps so common in the past?

In the past, headphones were used with lots of different source devices (turntable amps, receivers, radios) that maybe weren’t all that amazing at using a standard level of power output. Consequently, sometimes you’d go from using your headphones in one device to accidentally overloading and damaging them with another device. High-impedance headphones that are capable of resisting high voltage were more popular, and many manufacturers designed their higher-end professional options around this particular issue.

When people started to listen to portable devices like Walkmans, MP3 players, and computers, the need for headphones with high impedance was limited mainly to dedicated setups. However, people still wanted to use their expensive headphones with their new sources. When they did, it was very common to suddenly experience a very low maximum volume. In that instance, a dedicated amplifier was necessary to boost the gain enough for the headphones to work properly.

Plumbing metaphors and electricity

So, in order to get enough juice to your headphones, your source needs to be able to handle the job. Several factors work against you, including the headphones’ innate tendency to resist electricity and their power requirements.

Electric circuits are a lot like a water system. When you think of “current,” think of the rate water flows through the pipes. When you see “voltage,” think “water pressure,” and when you read “impedance,” think about how narrow the pipes are (which constricts the flow of water a certain amount). It’s not a perfect analogy, but it works for what we’re talking about. When you want to pump a certain amount of water out of a reservoir, you’ll need to know the previously mentioned things to determine what it’ll take to get it.

For headphones to work properly, you need to have at least that amount of “water” at all times. While you might be okay waiting for a minute or two while you fill up a bucket at a hand pump, your headphones can’t wait for the right amount of power to build up.

That’s where an amplifier comes in. Using its own power (or reservoir, if we’re going to continue this analogy), it can boost the signal from a source to satisfy the headphones’ requirements.

What is the decibel scale?

Editor’s note: This will get really dry and textbook-y so if you just want some common examples, skip to the last two paragraphs of this section

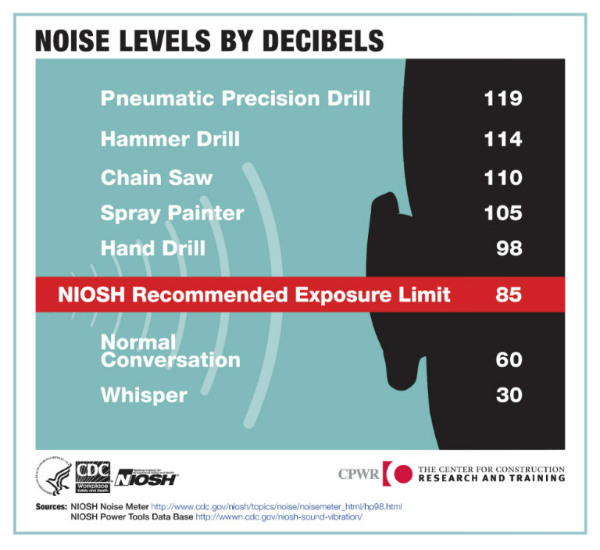

Do you know what a decibel (dB) is? It’s okay if you don’t, we’re only talking broad strokes here. It’s just a ratio of two values, one being the reference. The dB scale is logarithmic, like our hearing; every time you increase the power by 10dB, you’re increasing the power output in watts 10 times over. A 100dB signal is ten times more powerful than a 90dB one and 100 times as powerful as an 80dB signal. While the perception of loudness can’t be measured objectively, we do know that humans perceive a change in 10dB to be a change of roughly 2x in loudness. 70dB is twice as loud as 60dB, four times as loud as 50dB—you get the idea. If you’re wondering what level you should be targeting when you make your calculations, I usually say 85dB simply because it’s loud but not so loud as to give you noise-induced hearing loss that quickly.

So, remember when I told you to write down that sensitivity number? That’s how loud the headphones will get when there’s one milliwatt of current applied to it; usually, this is pretty loud—a level you shouldn’t be listening to anyway—but it’s how we determine the baseline for figuring out how much more power needs to be applied to raise or lower the volume. By using Ohm’s law and applying what we know about decibels, we can figure out the current needed to get a certain volume level.

Essentially, the math works like this: for every 10dB you want to increase the volume, you need to apply ten times the power. For every 10 dB you want to decrease the volume, you need to reduce it to 1/10th the power. Easy enough, but what about the voltage? Basically, it’s as easy as plugging your numbers into this equation: Voltage(Vrms)=√[Power in Watts*Impedance]. Just remember, because we’re dealing with milliWatts, be sure to divide any number in front of mW by 1000 first.

Let’s look at two different theoretical examples. Headphone A has an impedance of 300Ω and a sensitivity of 85dB/mW. While it only needs 1mW at 0.55Vrms to reach a comfortable listening volume of 85dB, in order to increase the level on your hifi setup, you’d need to pump 10mW at 1.73Vrms to reach 95dB. That’s a lot of juice and not something your smartphone can really do. Given that smartphones don’t output that kind of power, you’re going to want to use an amp with headphone A.

Alternatively, Headphone B was designed for smartphones and has an impedance of 32Ω and a sensitivity of 105dB/mW. This set will only need 0.01mW at 0.02Vrms to reach 85dB and will be much easier to run off of just about any source because it is so efficient. You will set your headphones on fire and deafen everyone around you long before you reach power levels that would require an amplifier with Headphone B.

But what about cables?

If you find yourself asking whether cable size being too small would make a difference, you’d be right! However, the vast majority of cables available to you will be more than sufficient to support what you need. This is especially true for headphones, which typically have much lower power requirements and shorter cables than speakers.

We’ve covered issues regarding cable quality and specs before, and you should definitely read up on it! If nothing else, the coat hanger cable experiment is entertaining and demonstrative of the fact that you don’t need to shell out for expensive cables to get rock-solid audio quality. High-quality materials and interconnects are only needed if you’re planning on exposing them to the elements. If you’re staying indoors in a climate-controlled room? Go ahead: cheap out on cables.

So, do you ever need a headphone amp?

If it wasn’t obvious before, very few headphones out there require a lot of juice to work properly. It’s really only when you start getting into the world of audiophile-grade cans that you start to see models that require a dedicated amplifier to work the way their designers intended. That’s because most headphones—even the newer high-end ones—are being designed for use with things like iPods, smartphones, and Bluetooth, which are low-power devices.

What about regular speakers?

If you’re wondering about speakers rather than headphones, the answer is much simpler: If your speakers don’t have a power cord (passive speakers), you need an amplifier. If they do have a power cord (active/powered speakers), you don’t—they already have built-in amplification. Most computer speakers, modern bookshelf speakers, and Bluetooth speakers are active and don’t need an additional amp.

FAQs

No, a PC cannot serve as a direct replacement for an amplifier. While PCs can adjust volume through software, they cannot provide the power needed to drive passive speakers. Some people confuse digital volume control with amplification, but they’re different things—amplification requires actual power delivery to the speakers.

For most users, a separate DAC (Digital-to-Analog Converter) isn’t necessary as modern devices like smartphones, laptops, and gaming consoles already include good-quality DACs. You only need a separate DAC if you’re experiencing specific audio issues like interference, static, or distortion from your current source.